Earlier this year, California Assemblyman Rob Bonta (D-Oakland) introduced AB 1793 to facilitate and streamline cannabis record clearance for those eligible under the Adult Use of Marijuana Act (AUMA, which voters passed as Prop. 64).

Since the bill has become law, California communities must now hold the state Department of Justice, local district attorneys, and local public defenders accountable for implementing cannabis record clearance, so that the records of all who qualify are proactively and transparently submitted for reduction or expungement by July 1, 2020.

AB 1793 is a follow-up bill meant to guide and initiate the cannabis record clearance components of the AUMA, known first for legalizing the recreational use of marijuana for adults at least 21 years of age in 2016. The AUMA made some attempt to apply marijuana legalization retroactively, allowing for four cannabis-related felony convictions to be reduced and many more cannabis-related misdemeanors to be expunged, since they are no longer criminal violations under California state law. However, the AUMA did not provide for how people would be made aware of their eligibility, let alone successfully navigate the record clearance process on their own time and dime.

To these ends, AB 1793 demands that the California Department of Justice provide district attorneys a list of all eligible records in their respective counties by July 1 next year and that all eligible records be proactively submitted to the appropriate court for reduction or expungement by July 1, 2020.

The bill creates an automated, top-down process that does not discriminate based on a person’s legal and financial resources, benefits the maximum number of our community members, and helps to facilitate a sustainable transition from failed criminal prohibition to the legal regulation of cannabis in California.

Indeed, international human rights standards and best practices, drawing in part from some of the largest international commission reports on the global “war on drugs” suggest that the transition from prohibition to legalization must include the removal of criminal penalties, civil penalties, and social stigma suffered by those harmed by decades of failed criminal enforcement. For cities in California, and for cannabis prohibition nationally, we know that the populations most affected are our working class communities and people of color—African Americans and Latinx people in particular. We also know that drug convictions—felonies especially—can be a lifelong drag on individuals and their families, particularly under the brutal cost of living that defines the entire San Francisco Bay Area.

As illustrated in the recent passage of Amendment 4 in Florida that reinstates voting rights to 1.2 million people with felony convictions, drug felonies can strip people of their ability to vote, access financial aid for school, access housing assistance, or their ability to apply for employment in any number of careers. These “civil penalties” such as felon disenfranchisement, are a central manifestation of what Michelle Alexander famously called the “New Jim Crow” in 2010, where people of color are effectively denied equal rights and protection under the law through their disproportionate criminalization.

AB 1793 is one potentially effective measure to bring California in line with appropriate international standards, and to engage in meaningful restorative justice practices.

Although AB 1793 is now law, its success ultimately depends on the willingness and ability of district attorney’s offices to fulfill their clear responsibilities under the bill, in full view of the public, without burdensome delays, protests over individual cases, or protests over the general legality of proactive record clearance.

While AB 1793 requires that the Department of Justice keeps an updated online database of basic statistics (Section 1-F), no such requirement exists for individual counties. In other words, it will be up to communities to hold their own local officials accountable for effectively, efficiently, and transparently meeting their responsibilities under AB 1793.

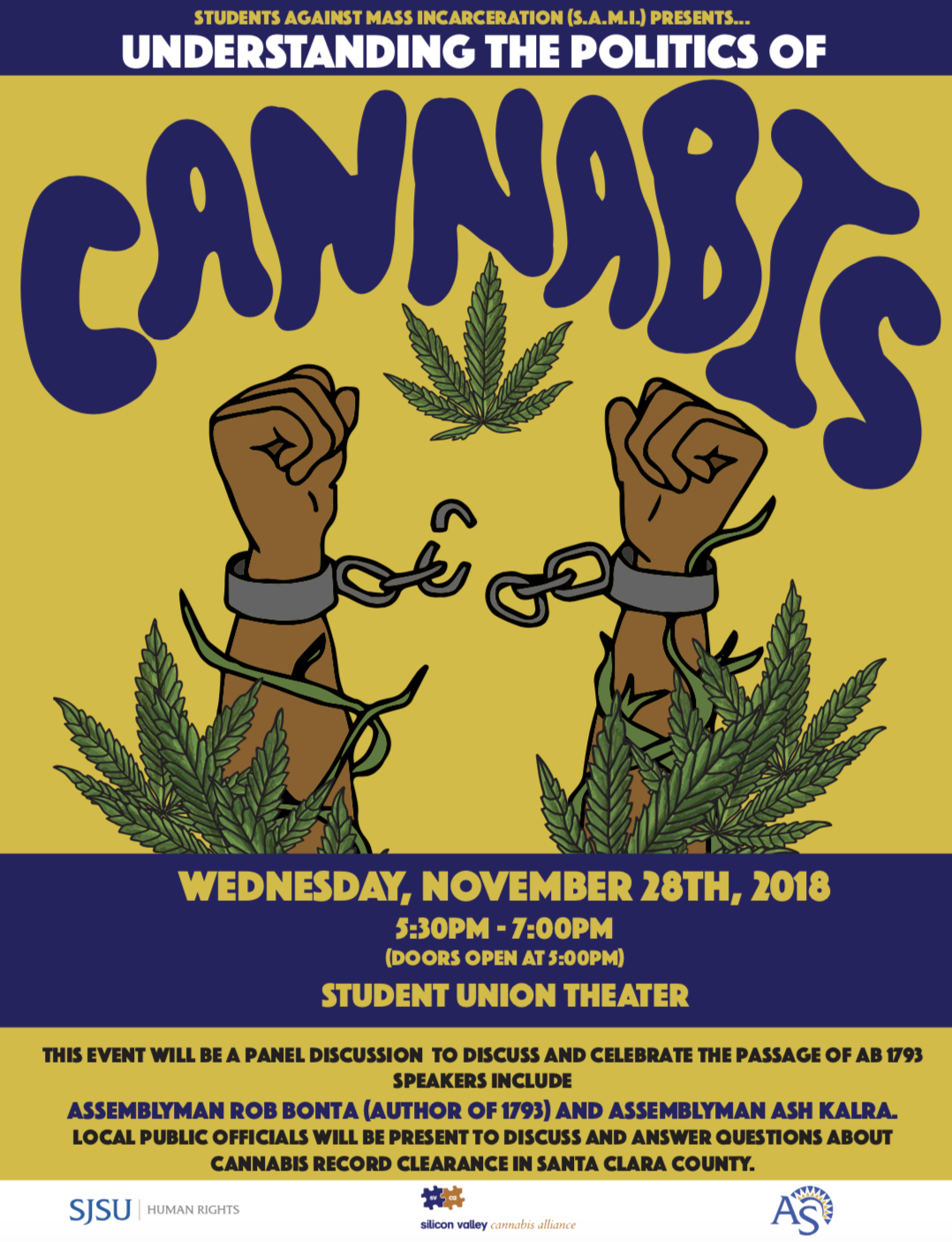

Toward this end, SJSU Students Against Mass Incarceration (SAMI), the SJSU Human Rights Collaborative, and the Silicon Valley Cannabis Alliance organized a public educational forum on cannabis record clearance for Nov. 28 in the SJSU Student Union Theater from 5:30 to 7pm (doors open at 5pm).

The forum will featuring AB 1793 author and Assemblyman Bonta, Assemblyman Ash Kalra, a deputy district attorney and deputy public defender for Santa Clara County, and Critical Legal Studies scholar and Human Rights Collaborative member, Edith Kinney.

This panel of public officials and experts will serve to educate the public on cannabis record clearance under the AUMA and AB 1793, answer audience questions on cannabis record clearance, and have a public conversation on how cannabis record clearance can be realized in Santa Clara County. The forum is free and open to the public, and will be a deliberate step toward achieving the implicit and explicit goals of AB 1793 to help as many of our community members as possible, as soon as possible.

William Armaline, Ph.D, is the director of the San Jose State University Human Rights Collaborative and a member of the San Jose-Silicon Valley NAACP executive board. Diana Varela attends San Jose State, where she helps lead a group called Students Against Mass Incarceration. Opinions in this article are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those of San Jose Inside. Send op-ed pitches to [email protected].

This looks like a tempest in a teapot. I had two traffic tickets from the ’80’s expunged. Now I have a totally clean record. Yay! (But my car insurance didn’t go down as much as I’d hoped).

Anyone with a cannabis (or similar) conviction can apply to have it expunged. A judge looks at the request, and if there’s nothing unusual and there are no extenuating circumstances, it’s automatically expunged from one’s record.

It costs something for the clerical work, but anyone can afford it.

So really, what’s the problem? SND?